Game Changers: Assembly for the Arts CEO Jeremy Johnson on growing Cleveland's creative industries

Source: WKYC 3

Abstract:

CLEVELAND — Jeremy Johnson spent more than three decades living on the east coast before returning to his hometown last year to take on an exciting new role.

“I feel like I’ve come back to Cleveland. I recognize the street names, but the city looks different. It feels different. The leadership is different. The people have a certain excitement about them,” Johnson told 3News anchor Dave Chudowsky in a recent interview.

FRONT International 2022 Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art Kicks Off This Saturday

Source: Cleveland Scene

Abstract:

The second edition of the free, summer-long, region-wide festival, FRONT International, opens this Saturday July 16th with 30-plus exhibition sites in Cleveland, Akron, and Oberlin featuring work by more than 100 national, and international artists, and runs through October 2, 2022.

FRONT kicks things off with a block party on Cleveland Public Square, hosted by DJ Red-I and featuring performances by Free Black, Sadhu Sounds, Hello!3D, Da Land Brass Band, Blakk Jakk Dance Collective, Mellow Man Funk, The Katy, and FRONT 2022 artist Asad Raza.

Cleveland’s Summer of Arts 2022: Top 5 Events to Check Out

Source: Places.Travel

Abstract: When you say art, we say Cleveland! This summer, things are going to get pretty artsy up in the Land. From July through August, the city will come alive with outdoor concerts, public art installations, special exhibitions, and plenty of opportunities to get involved in the local arts scene.

Cleveland’s Summer of Arts and Culture: A Cultural Empowerment Masterpiece

Source: Places.Travel

Empowering people through the arts. It’s something that resonates with every single soul on this planet. From the music we listen to, to the paintings that adorn our walls, and even the books we read – art is a part of who we are.

And Cleveland knows this. Cleveland breathes this. The Land is committed to empowering people through advocacy, activism, education, and resources to promote arts and culture. It’s what we do, it’s what we’re known for, and it’s why we’re so excited for the upcoming Summer of Arts in 2022, powered by Cuyahoga Arts & Culture.

Meet the 65-person Leadership Cleveland class of 2023

Source: Crain’s Cleveland

Abstract:

The Leadership Cleveland class of 2023, announced Friday, July 8, by the Cleveland Leadership Center, comprises 65 executives and leaders from the public, private and nonprofit sectors of Northeast Ohio.

Members of the class will take part in a 10-month program aimed at exploring “challenges and opportunities facing Northeast Ohio” with a goal of inspiring the leaders “to use their newfound knowledge and connections to advance our region,” the Cleveland Leadership Center said in a news release.

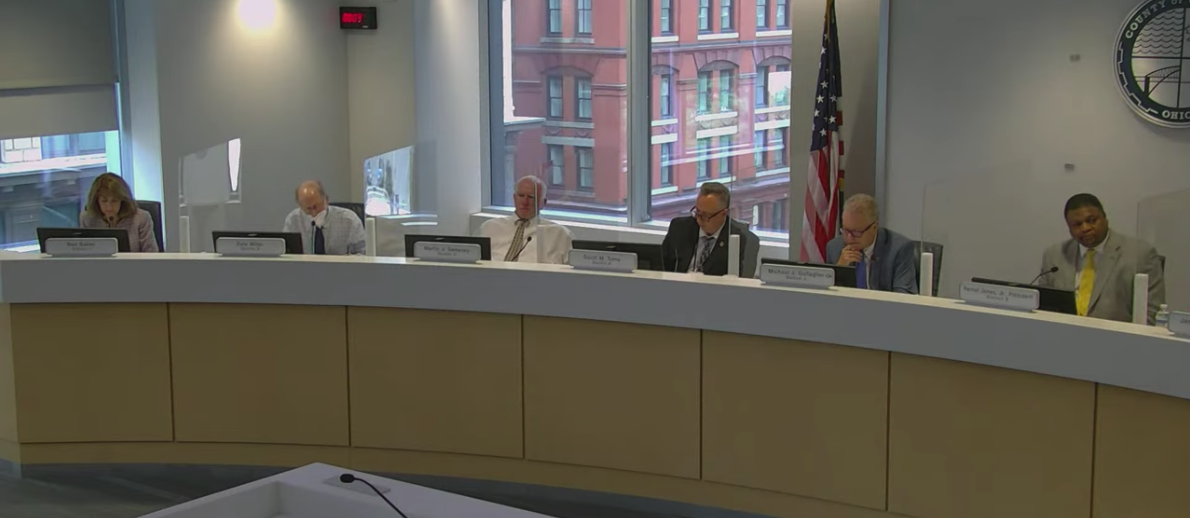

Cuyahoga County approves $3.3m for relief and reinvestment into Northeast Ohio art and culture

Source: News 5 Cleveland

Abstract:

The Cuyahoga County Council approved $3.3 million of American Rescue Plan Act dollars to Cuyahoga Arts and Culture and Assembly for the Arts. It will be split evenly between the two groups. Jeremy Johnson is the CEO of Assembly for the Arts. It is a group that advocates and unifies the voices of creatives throughout greater Cleveland.

Cuyahoga County authorizes $3.3 million in federal COVID relief money for the arts

Source: Cleveland.com

Abstract:

CLEVELAND, Ohio — Cuyahoga County is investing $3.3 million in money for the arts from ARPA, the federal government’s American Rescue Plan Act.

County Council voted Tuesday to authorize awarding up to $1.65 million in ARPA funds to Cuyahoga Arts and Culture, the agency that supports the arts by distributing proceeds from the county’s cigarette tax to cultural organizations.

Council also voted to authorize granting the same amount to the nonprofit Assembly for the Arts, an umbrella group for Cleveland’s nonprofit and for-profit cultural industries, to support artists and creative businesses.

Cuyahoga County arts organizations getting $3.3 million in ARPA funding

Source: ideastream

Abstract:

Cuyahoga County Council unanimously granted two arts organizations $1.65 million apiece in American Rescue Plan funds. Cuyahoga Arts & Culture (CAC) and Assembly for the Arts will use the funds to help the creative economy, which is still recovering from the coronavirus pandemic. CAC reports that organizations it works with saw a $171-million drop in revenue during the first 22 months of the pandemic.

Jeremy Johnson, CEO of Assembly for the Arts, said he hopes these county funds are a harbinger of more public investment in the arts – especially after more than two years of the pandemic. Arts advocates are also requesting ARPA support from Cleveland.

Cuyahoga County arts organizations getting $3.3 million in ARPA funding

Source: WKSU | By Kabir Bhatia

Abstract:

Cuyahoga County Council unanimously granted two arts organizations $1.65 million apiece in American Rescue Plan funds. Cuyahoga Arts & Culture (CAC) and Assembly for the Arts will use the funds to help the creative economy, which is still recovering from the coronavirus pandemic. CAC reports that organizations it works with saw a $171-million drop in revenue during the first 22 months of the pandemic.

Jeremy Johnson, CEO of Assembly for the Arts, said he hopes these county funds are a harbinger of more public investment in the arts – especially after more than two years of the pandemic. Arts advocates are also requesting ARPA support from Cleveland.

Cuyahoga County Approves $3.3 Million

Cuyahoga County Approves $3.3 Million in Funding Made Possible by American Rescue Plan Act to Cuyahoga Arts & Culture and Assembly for the Arts to Support the Creative Economy

Funds will support arts nonprofits, creative workers, and for-profit creative businesses

CLEVELAND (July 5, 2022) – Today, Cuyahoga County Council awarded $3.3 million in funding made possible by the American Rescue Plan Act to Cuyahoga Arts & Culture and Assembly for the Arts to help bolster the creative economy, a sector hit hard by the ongoing pandemic.

Cuyahoga Arts & Culture and Assembly for the Arts worked collaboratively to secure support from Cuyahoga County Executive Armond Budish and County Council President Pernel Jones, Jr. County Council approved the funds by a unanimous vote. The $3.3 million will be evenly split between CAC and Assembly ($1.65 Million to each). CAC will subgrant to arts nonprofits and Assembly will subgrant to artists and creative businesses.

“Cuyahoga County is known for its vibrant arts and culture community, which is sadly still suffering the negative effects from the COVID-19 pandemic,” said County Executive Armond Budish. “We are providing additional funds to ensure that arts and culture survive and thrive. It is our goal to help the entire creative economy continue their artistry in Cuyahoga County and remain the inspirational community asset they have always been.”

Council President Pernel Jones, Jr. added, “County Council is pleased to support arts and culture with these funds, made possible by ARPA, especially knowing they will reach nonprofits, businesses and artists living in every Council District.”

CAC’s Executive Director Jill M. Paulsen said the creative sector was hard hit by the COVID-19 economic downturn and has yet to recover. Organizations funded by CAC reported more than $171 million in lost revenues from March 2020 through December 2021, impacting the employment of more than 5,000 people.

“We are thrilled to be able to grant $1.65 million from the County to local arts nonprofits when they need it the most. This allocation from County Council and the County Executive demonstrates they value the work our arts and culture nonprofits do to contribute to quality of life in Cuyahoga County,” Paulsen said. “We know the organizations we fund are grateful, and on their behalf, we say thank you to the County.”

“The arts and culture sector was the hardest hit of all industries during the pandemic,” said Jeremy Johnson, President and CEO of Assembly for the Arts. “We thank the County Executive and the County Council for helping artists and small creative businesses get back on their feet to reignite the diverse cultural jobs and services that are the backbone of a $1.9B creative regional economy.”

Soon both organizations will announce processes to apply for funds. CAC will make grants to eligible CAC grant recipients that have a primary mission of arts and culture. For-profits and creative workers can apply to receive funding from Assembly for the Arts.

Previous CAC grant recipients can request a notification when funding is available here. Individual artists and small cultural businesses can visit www.AssemblyCLE.org/arpa for more information.

Together, CAC and Assembly (through its predecessor organization Arts Cleveland) have secured $7.8 million in recovery funding for the creative economy through American Rescue Plan Act and Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act funds provided by Cuyahoga County since 2020.

Cuyahoga Arts & Culture (CAC) is one of the largest local public funders for arts and culture in the nation, helping hundreds of organizations in Cuyahoga County connect millions of people to cultural experiences each year. Since 2006, CAC has invested more than $218 million in 445 organizations both large and small, making our community a more vibrant place to live, work and play. For more information, visit cacgrants.org.

Assembly for the Arts is a 501c3 nonprofit organization that serves as a unifying voice for greater Cleveland’s creative sector. Assembly strengthens and supports those who create, present, experience and appreciate all forms of arts and culture. The organization is attentive to the needs and impact of BIPOC artists, nonprofits, and small creative businesses. Assembly seeks to expand the pie of financial, technical, and capacity support for the arts and cultural sector; and increase equity for BIPOC and historically disadvantaged communities within the sector. For more information, visit AssemblyCLE.org.